Upstate South Carolina’s commercial real estate market is facing a critical shortage of vacant land, according to Maggie Steck, broker in charge at Freedom Commercial. Steck, who has specialized in land sales across the region since 2020, says Greenville’s most desirable areas are now fully claimed, leaving developers with few options besides moving into riskier secondary markets with longer project timelines.

“Greenville is just totally sold out of land,” Steck says. “There’s no land left in the Greenville, South Carolina area. It’s a hot spot, and it’s gone.”

Steck emphasizes that this is not a temporary pause in listings or a cyclical dip. The supply crunch is a direct result of geography: nearly every parcel in Greenville proper has either been developed or is under contract. The only remaining opportunities are in more remote areas, such as northern Spartanburg County, and in smaller towns such as Greer and Duncan. These markets offer available acreage but entail higher risks and longer development timelines.

Why the Land Shortage Matters for Development

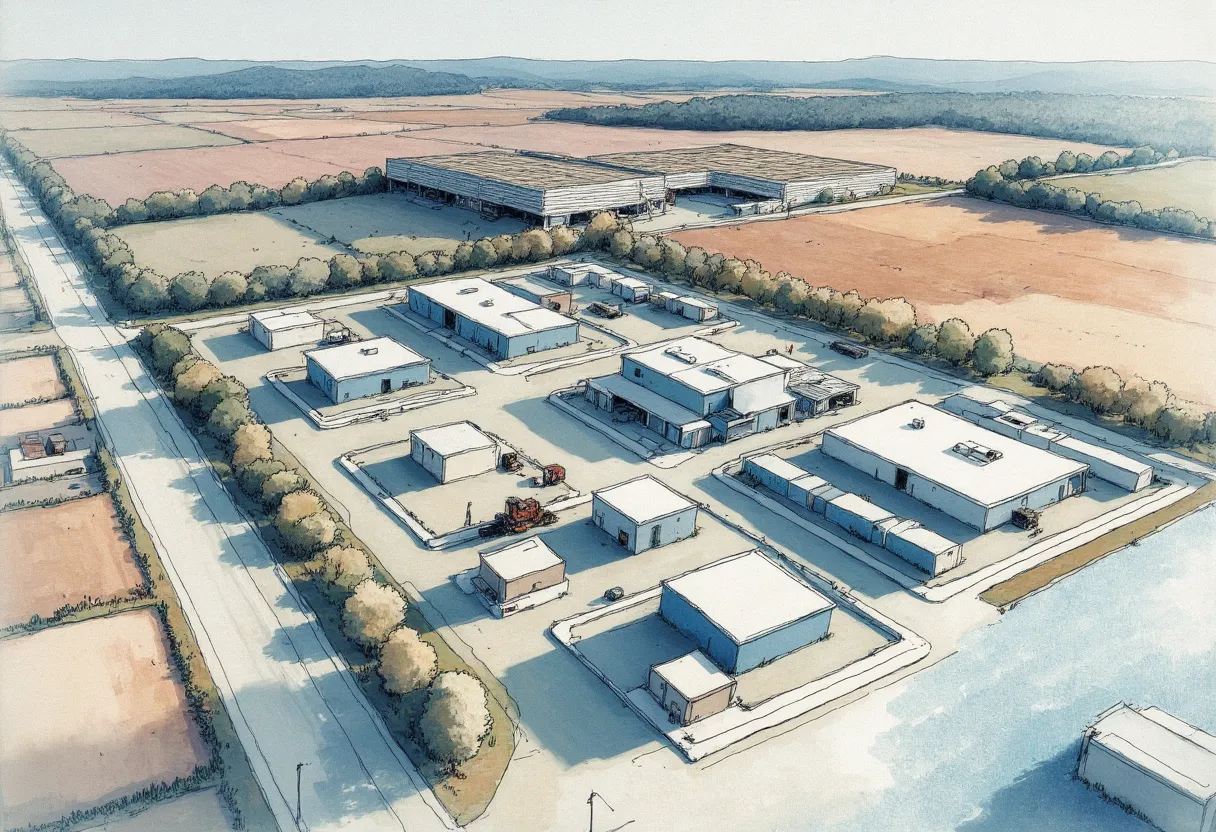

The shortage of developable land is reshaping how projects get financed and executed in the Upstate. When developers buy raw land in these outlying areas, they are responsible for installing infrastructure—roads, utilities, drainage—before selling finished lots to builders. This process requires millions in upfront investment, tying up capital for years before any homes are built or sold.

“I’ve got a 158-acre tract that I sold four years ago to one builder, and they sat on it for two years and didn’t want it,” Steck says. “I resold it with another builder out of Atlanta, and it’s taken two years to close the whole thing. So it’ll be four years by the time it’s over.”

This four-year commitment exposes developers to significant market risk. During that period, interest rates may rise, buyer demand may shift, and broader market conditions may deteriorate. Steck points to the 2006–2011 housing downturn as a reminder that long development horizons can turn profitable projects into financial liabilities if market conditions change. “Something like what happened back in 2006 through 2011 could happen again. We don’t know. So it’s a big risk for a developer to develop hundreds of acres.”

Builders Shift Risk to Developers

This uncertain environment is changing the way national builders operate in the region. Steck notes that major builders, who previously handled their own land development, now prefer to have independent developers handle the infrastructure work and associated risks.

“National builders really prefer to have the developer develop the land, and then they buy the lots from the developer,” Steck says. “But that puts all of the heavy-duty responsibility on the developer. He’s the one paying to develop, and it’s millions of dollars to develop.”

This approach shifts financial risk from builders to developers, who must fund all infrastructure costs and wait several years for a potential return. If market conditions decline during that period, developers could be left holding unsold lots and unrecovered costs.

Rising Costs Challenge Affordability

Beyond the supply issue, the economics of land and development costs are making it increasingly difficult to build homes at prices the market can support. Higher land prices and expensive infrastructure mean that even modest homes are becoming less affordable.

“With the land cost and the cost of development, it ends up costing a lot to build a home,” Steck says. “It all costs a lot of money, so it’s all risk. All has to flow together.”

Steck says that builders are now focused on smaller homes—typically 1,200 to 1,500 square feet—as the only way to keep prices within reach for buyers. However, even this strategy is being squeezed by high acquisition and development costs, which continue to climb as builders move into secondary markets.

Developers who bought land three or four years ago are in a better position, having secured lower prices and shorter timelines. Those entering the market now face higher land costs, longer project completion delays, and greater exposure to market volatility.

Spartanburg’s Rapid Growth and the Uncertain Future

As Greenville’s land inventory has disappeared, developers are turning their attention to Spartanburg County. Steck describes Spartanburg as “growing very fast,” despite initial doubts from some in the industry.

“The guys that I started with said, ‘Oh, Spartanburg, blah, blah, blah, it’s all industrial up there,’” Steck says. “Ryan’s from Spartanburg. He goes, ‘Wait, just wait. It’s going to grow fast.”

Steck’s prediction is coming to pass, with Spartanburg now experiencing the fast-paced development that Greenville saw several years ago. “People are complaining now that there’s too much building going on and traffic is terrible,” she says.

Whether Spartanburg can handle the volume of new development remains uncertain. The region is betting on continued population growth from the Northeast and Florida to sustain demand. However, the long development cycle—often four years or more—means that projects starting today may not deliver homes until 2028 or 2029. Developers must decide whether current migration trends will persist long enough to justify their investment.

A New Reality for Upstate Land Investors

For investors considering the Upstate South Carolina land market, Steck’s assessment is clear: the easy opportunities in Greenville are gone. What remains are riskier, longer-term investments in secondary markets, with higher upfront costs and no guarantee of strong demand upon project completion.

Success in this environment depends less on current market conditions and more on the region’s ability to sustain its growth trajectory for the next four to five years. Developers and investors must weigh the potential rewards against the reality of longer timelines, higher costs, and increased risk as the Upstate real estate landscape enters a new phase.